In Your Image: From Iceberg to Artist in Greenland

In Your Image: From Iceberg to Artist in Greenland

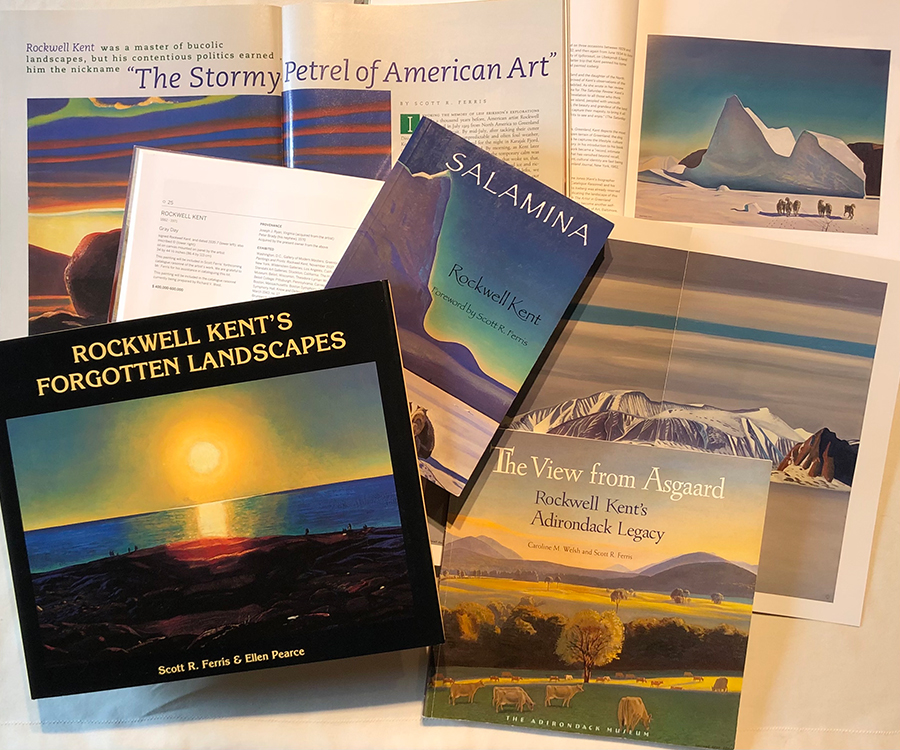

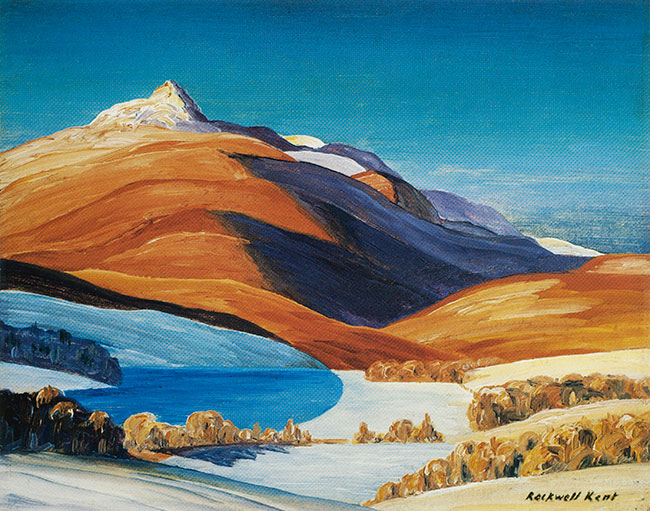

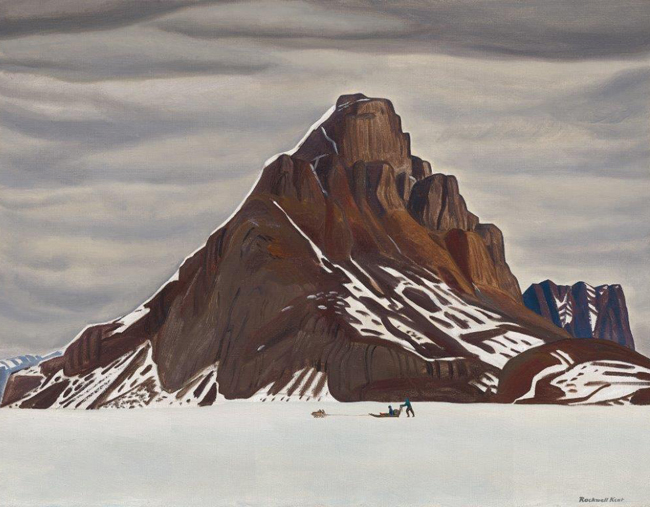

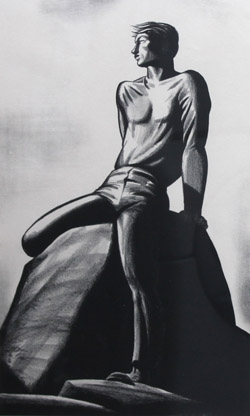

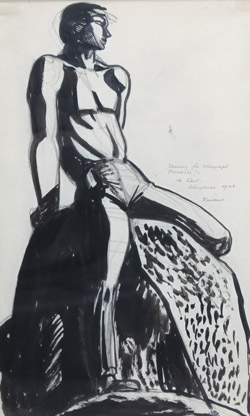

There has been some confusion regarding Rockwell Kent’s painting The Artist in Greenland. It has been assumed that the latter was painted in 1935 when in fact it was not created until 1960, as, in part, a copy of his painting Iceberg, as I will clarify below.

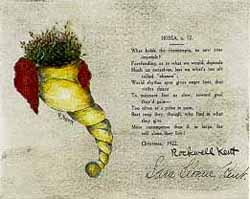

In a manner of prefacing… I possess a set of 35mm slides that depict Sally and Rockwell Kent hosting the annual birthday party for Rockwell, in June of 1960: a party which was attended by several people, including their friends Jacquie and Dan Burne Jones. In one slide, shot in the Kents’ bar, the painting Iceberg is displayed on the wall. Obviously the Joneses saw this painting. Having seen it they wished to add it to their growing Kent collection, however, it was already promised to J.J. Ryan, the artist’s major benefactor at the time.

What transpired next is that Kent decided to copy this painting, for the Joneses, though with some additions, as the artist clarified in his 31 July 1960 letter to the Joneses. In this letter Kent states: “I have removed the picture from the bar… I have begun work on the copy and am happy to learn that you give me a free hand with the dogs.” In this same letter he finishes by saying: “I will end this letter and go back to work on the iceberg picture.” He continues, after referencing J.J. Ryan and commenting on transferring Iceberg to him: “I would like to have the picture in shape for him to take back with him.” Iceberg is the painting that RK was copying for the Joneses. In Kent’s 10 July 1960 letter to Ryan he said: “The bar picture, which I had not intended to send, is marked as yours–for, since you would talk price, two thousand dollars.” (The sale and transfer of Iceberg is completed in September, as per an exchange of letters between Ryan and Kent on the 19th and 22nd.)

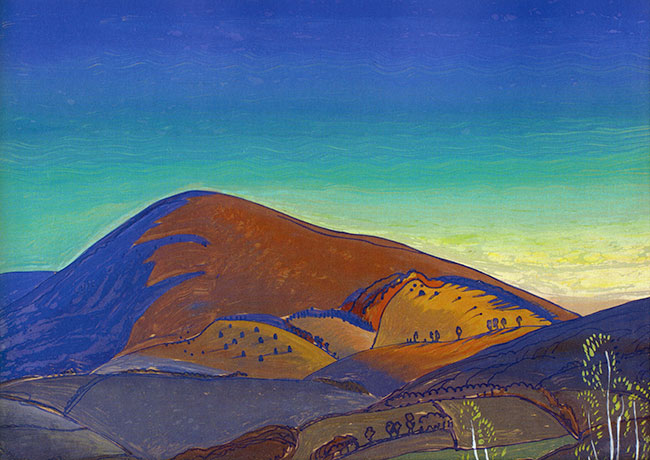

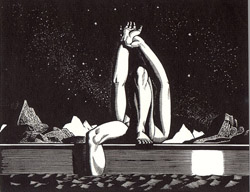

Continuing with the discussion about the development of what would eventually be titled The Artist in Greenland, Kent writes to the Joneses on 1 September 1960: “The recovery of my strength and energy, though steady, has been so slow that I have not yet been able to finish the iceberg picture.” Yet by 10 September 1960 he states: “On yesterday’s noon train from Au Sable Forks the two pictures, SUN GLARE and THE PAINTER IN GREENLAND [The Artist in Greenland]–packed, I believe, securely–left for their Chicago home with you. As I recovered my accustomed strength I was able to work more and more on the Greenland picture and finished it. And both pictures are so nearly like the originals–except for the dogs and me in the foreground of your picture, replacing and outnumbering in dogs the dog-team of the other–that I would find it quite impossible to detect the difference between the original and the copy.” (Herewith illustrated, you can see how Kent applied the landscape from Iceberg as a backdrop for The Artist in Greenland, yet added, as he said in his above letter, the figures.)

As a general statement regarding Kent’s practices, he mentions in his 31 July 1960 letter: “The original, like many of my paintings, is mounted on ply-wood.” The Artist in Greenland, unlike Iceberg, is not mounted on plywood. Other Greenland paintings that exemplify this practice can be seen in my book, Rockwell Kent’s Forgotten Landscapes. As you will read in the captions, all of the Greenland paintings are backed with plywood, except one. Having said that, I know of one instance where a painting that was mounted on board was removed, by a conservator, from the same. The documentation thereof and the remnants of its previous “life” are extant. There is no evidence of the same with regards to The Artist in Greenland.

Another practice common to this artist is that if he significantly altered a composition (which he often did) he would acknowledge the change by re-signing and sometimes re-dating the painting: sometimes burying the original inscription with over-paint or allowing both inscriptions to appear. There is no second signature on The Artist in Greenland.

In summation of the above evidence, I am confident that The Artist in Greenland was inspired by and thus became (in part) a copy of the painting Iceberg.

The Artist in Greenland has resided at the Baltimore Museum of Art since 1991; and Iceberg, is no longer in the J. J. Ryan Collection/Oak Ridge Estate, having sold at Christie’s in 2016.

In Review: The Other Rockwell Kents: An Introduction

In Review: The Other Rockwell Kents: An Introduction

“Some things have to be believed to be seen.”

Ralph Hodgson (1871-1962)

Rockwell Kent (1882-1971) was a renowned artist in the fields of painting, printmaking, book illustration, commercial design, and watercolors: so much so that his artwork was copied throughout his life: from students who wished to learn the master’s techniques, to copyists who mimicked his style.

Over the past several decades I have been presented with paintings (and occasionally works on paper) for which auction houses, galleries, museums and collectors have sought authorship confirmation. Many are documented, others are of questionable attribution. For those that are questionable, the works are often signed “Rockwell Kent”; sometimes rendered in a style similar to that of Kent; and occasionally the content — the assumed geographical location, for instance — recalls the work of our protagonist. (The file on these “non-Kents” has grown exponentially.)

Adding to the confusion, Rockwell Kent was not the only artist by that name. In the early 1900s he exchanged correspondence with his namesake: a man who was near the end of his career as a proofreader for the major New York City area newspapers, and as an amateur prose writer and printmaker [he lived 1858 to 1934]. Throughout the years the artwork by this gentleman has often been mistaken as that by the principal character in this essay. [For more information on the man see of one of my earlier In Reviews — “Addendum for the exhibition brochure, Generations,” in Essays.] There are, undoubtedly, other artists in the “annals of creativity” by the name Rockwell Kent.

What I wish to accomplish in this edition of In Review, is to introduce you, the reader, to the muddied waters of authentication. And illustrate how, by way of descriptive and visual comparisons, dubious attributions could be problematic for academia and the art market of today. Outright copying of the artist’s work and misattributions are nothing new in the Kent world, as we will see below. I will not be illustrating every “non-Kent” that I have on file as that would require a much lengthier publication. Let’s begin with examples of situations that Kent personally experienced.

Admiration or Pirating

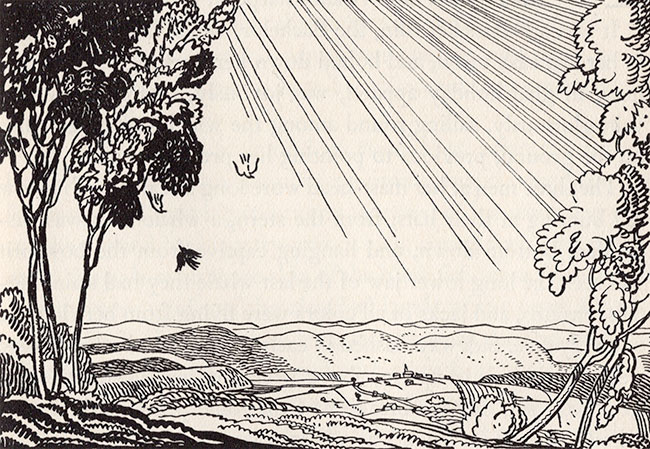

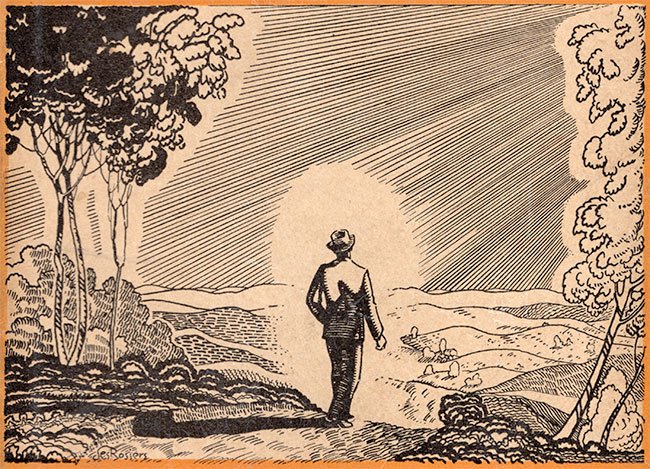

In a March 10, 1934 letter to Howard Lewis of Dodd, Mead and Company, Inc., Rockwell Kent wrote: “Here is proof of the illustration on page 705 of the trade edition of ‘Moby Dick.’ I should like to be present when the young prize fighter explains the likeness between his drawing and mine.” (fig. 1) To which Lewis responded (March 12th, 1934): “Thank you for sending the proof of the illustration from ‘Moby Dick’ which Mr. Des Rossiers [sic. des Rosiers] admired so much that he used it for a jacket drawing for Amos the Wanderer, by W. B. Maxwell, which we published in 1933 [sic. 1932]. Mr. Des Rossiers came in this morning and he informed me that he will make his peace with you in person. He could hardly deny that the two pictures were practically identical.” (fig. 2) [Dodd, Mead and Company went on to publish Kent’s autobiography, It’s Me O Lord in 1955.]

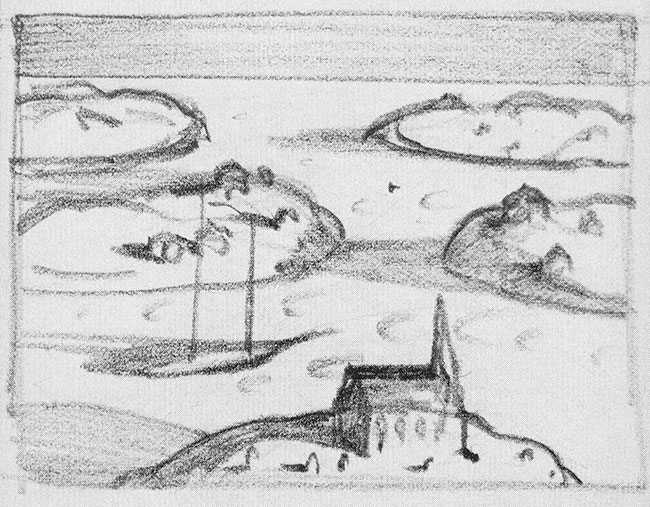

And then in 1965, in a November 23 letter to Richard Larcada [Kent’s gallery representative], the artist wrote: “It may amuse you to know that the Wickersham Gallery two weeks ago was showing — and still may be showing — a little 12 3/4″ x 15 1/2″ pastel of a winter scene titled ‘Greenland Coast,’ allegedly signed by me and dated 1907. (fig. 3) The picture was reproduced in the catalog, and its price, as ascertained by the friend who sent the catalog to me, was $1,700. I wrote the Director, Mr. June, that I had never in all my life used pastels, that I have never seen the place that was pictures [sic.], that it was not, as in the catalog it was called, ‘Greenland Coast’; and that I had not seen the Greenland coast until twenty-one years after the date ascribed to the picture. In short, it is a complete fraud. I was interested in reading in the New York Times of a few days later that picture frauds are so prevalent in New York nowadays that legal action against them is being considered. Incidentally, Mr. June has not replied to my letter. I wish I knew how to give the matter publicity. Such frauds deserve to be exposed.”

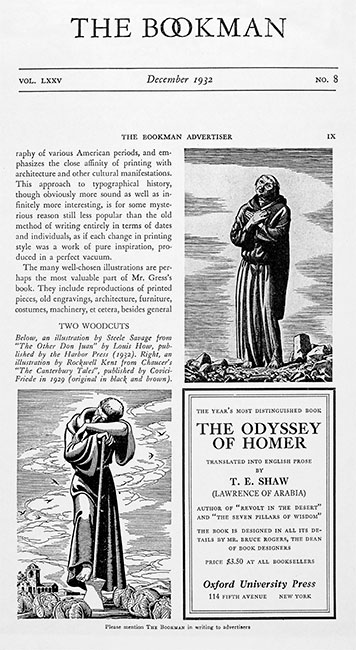

From an historical perspective many other examples abound. Harry Cimino’s illustrations for Seven Horizons, and Edward Shenton’s drawings for This Is My Country and Northern Lights paid homage to Kent’s creativity. Shenton’s illustrations for Northern Lights virtually duplicate many of Kent’s images from N by E. (fig. 4 and fig. 5) Artworks by other artists have often been and still are mistaken to have been rendered by Kent. In 2004 Swann Galleries, of New York, sold a Steele Savage drawing as a Kent, noting “stylistic comparisons with other drawings.” Unbeknownst to Swann, The Bookman, in a December, 1932 issue, illustrated the drawing they were selling — from Louis How’s, The Other Don Juan — comparing it with Kent’s illustration of a monk, from Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales. (fig. 6) [The Bookman caption title incorrectly refers to the drawings as “two woodcuts.” In Kent’s case this is a frequent misnomer: moreover, many of his drawings were rendered with brush and ink.]

From One…

By examining one painting of dubious authorship we are often led down paths towards many.

Early in the previous decade I was shown an unframed oil on canvas board of a landscape, purportedly depicting a view of Mount Equinox, near Arlington, Vermont: one that is signed “Rockwell Kent.” The painting was in the hands of a prominent New England art dealer. I was informed by the dealer that an associate of his, whom he described as a “picker,” — someone who seeks out art and antiques from primary sources — found the painting at a flea market in New Hampshire. The dealer expressed doubts, to me, about the attribution. Another individual later saw the painting, accepted the attribution, and proceeded to acquire the work. The painting has since appeared in several publications and exhibitions as by Rockwell Kent (1882-1971).

The painting, referred to as “Vermont Study” (fig. 7), certainly has some similarities to Rockwell Kent’s oil paintings of Mount Equinox, as well as to a reverse painting on glass (also executed by the master). Yet it likewise has similarities to paintings that are distinctly not by Kent. Perhaps the most damning evidence against a Kent attribution, though, is the distinct difference between this painting and a study that was handed down from Kent’s first wife, Kathleen, to one of her grandsons. Let’s begin with the latter painting, first.

Known Kents

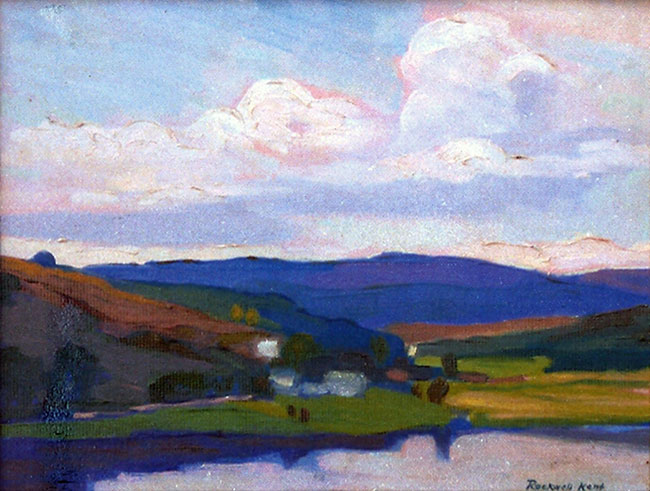

The Kent family painting, unsigned, — authenticated by Kent’s son, Gordon, in a letter on the verso depicts a view toward Mount Equinox, in winter. (fig. 8) The sky is heavily overcast, and the colors, muted. The pigments are raw; the elements, basically defined. The oil paint is lightly applied on a wood board: quickly sketched in with broad and narrow and abrupt, horizontal and vertical brushstrokes. In short, it is typical of Kent’s approach to laying out the foundation of small studies, and often times larger, what would become finished compositions: a method perhaps inspired by one of his earliest mentors, William Merritt Chase.

In contrast, due in good part to the medium, the reverse painting on glass glistens. (fig. 9) The pigments are brushed on flat and smooth, on the textureless pane of glass. The compositional elements, and hues, share visual qualities with some of Kent’s earlier Berkshire (Massachusetts) landscapes.

Similarities and Differences

“Vermont Study” has the glistening effect that we see in the reverse painting on glass: as if the pigment was mixed with linseed oil. Any sheen that we see in Kent’s Vermont paintings (like others from his greater oeuvre) is more a result of the varnish that he used to cover his completed works.

Kent frequently created three predominant visual tiers, or planes — fore, mid and background — in his compositions: with compositional elements within those planes that are appropriate for that space–a height or width ratio that represents the distance of the given element: such as a field or trees, for instance. “Vermont Study” breaks those planar boundaries with elements that stretch from one plane to the next–the mid ground field overlaps with the foreground field. It lacks the definition of the frontal plane we commonly see in Kent’s Vermont (and other) compositions. What serves as a frontal plane in “Vermont Study” are two diagonals, that originate from the left and right edges of the composition, that meet in the center. The form on the left displays a crude, furrowed effect, atypical of Kent.

The paint is heavily applied throughout “Vermont Study.” And long, continuous brushstrokes and serpentine patterns, like wrappings, (one stacked above another) form the distant mountain. Kent’s application of pigment is lighter, freer. And within his compositions he often contrasts abstract “patches” against well defined elements that he wishes to highlight — a blurred hedgerow focuses the eye toward a tree, deer or mountainside. There are no such contrasting elements in “Vermont Study”: contrasting colors, perhaps.

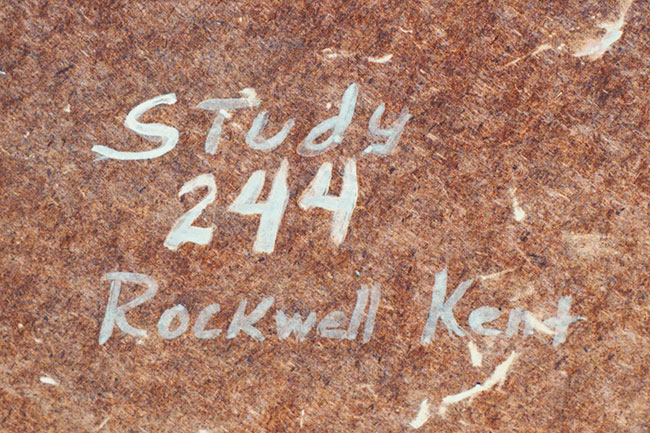

In “Vermont Study,” the foliage and mountain peak become little more than muddled brushstrokes. This manner of rendering shares characteristics with a so-called Greenland painting of equally questionable attribution (inscribed on the verso: “Study 244 Rockwell Kent”). (fig. 10 and fig. 11)

From One, the Many…

Another painting that had been attributed to Rockwell Kent (1882-1971), — which has been referred to as “Adirondack Landscape” (fig. 12) — possesses striking similarities to “Vermont Study”; and in its similarities pulls us further away from an association to Kent’s work. It, like “Vermont Study,” is an oil on canvas board. It is composed, in part, by glistening, sweeping brushstrokes and patterns that provide the contours of hills and mountains: with a palette further afield than that which is common to Kent. And like “Vermont Study,” an element, the clouds in this case, are heavy with impasto.

“Adirondack Landscape,” like “Vermont Study,” is rendered on (maker labeled) canvas boards. The former painting bears a two-toned brown, rectangular label for “H.R. Giger, Ltd./New York, Boston,” with a letter “G” within a crest, above this text. And the canvas board for the latter painting bares a red, scalloped, circular label — more like a stamped seal — which reads: “J.H. Hatfield Hand Ground Artists’ Colors. Canton Jct., Mass.” (Both, Boston area makers or suppliers.) Kent rarely used canvas board, and those that are known do not bear these labels. Kent used a “Royal Crest Illustrating Board,” manufactured by Hurlock Bros. Company, Inc., from Philadelphia, for his commercial illustration, “Science Explains the Fish Deluge”; and the canvas boards for his Greenland, figural works, Northern Exposure and Southern Exposure, give the impression of being homemade: a simple board covered with canvas, with no labels on the versos.

“Vermont Study” and “Adirondack Landscape” are finished, generic works that could represent a variety of geographic locations. The Kent family painting, in its depiction of the view of Mount Equinox, is visually representative of Kent’s other Vermont landscapes; and its manner of construction — the technical aspects of its creation — has precedent in innumerable paintings that come before it.

Belief Through Association

“Vermont Study” was (perhaps still is) on view at the Bennington Museum, in Bennington, Vermont: now framed. The frame is, or is in the style of, the frame that was on the Alaska Impression painting with which it has been juxtaposed. The current frame on the Alaska Impression is contemporary; and its original frame appears to have been re-utilized to display a reverse painting on glass referred to as “Baby with Blue Bird” (see The Magazine Antiques, July 2005, p. 73) — a posthumously completed work: the artist had not painted in the sky. Perhaps the purpose of reusing the Alaska Impression frame was to provide the viewer with a sense of what the painting on glass would have looked like when it was originally displayed. (Both paintings circa date to 1919-1920.)

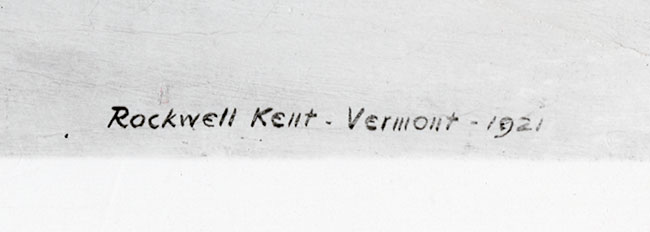

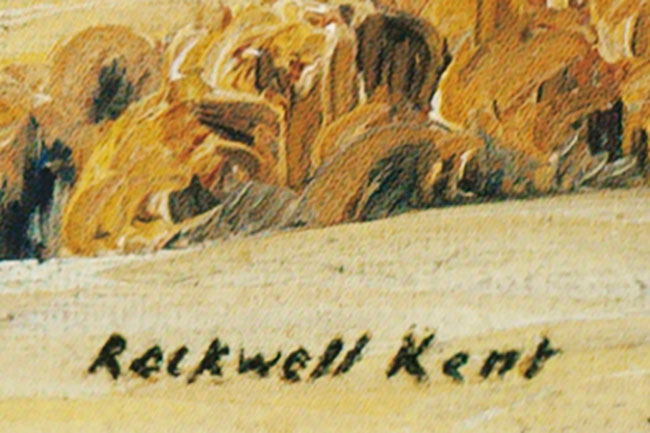

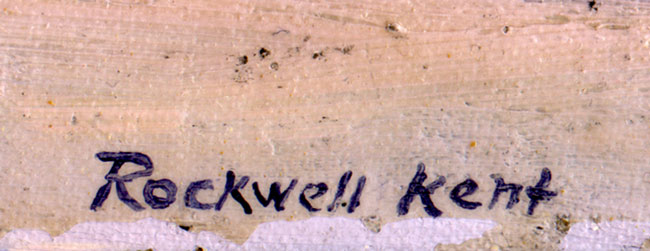

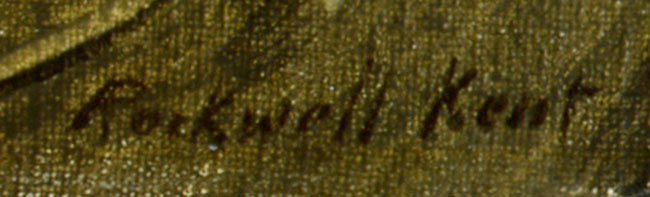

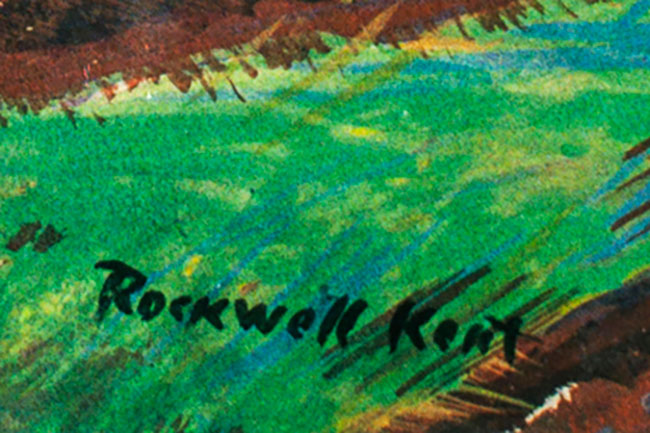

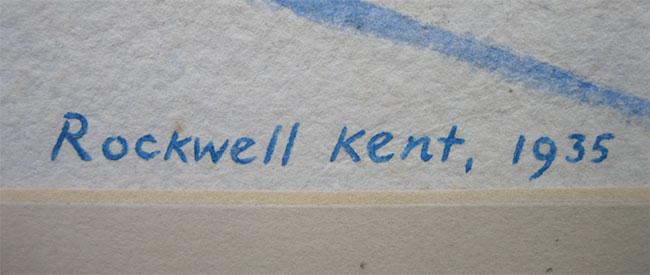

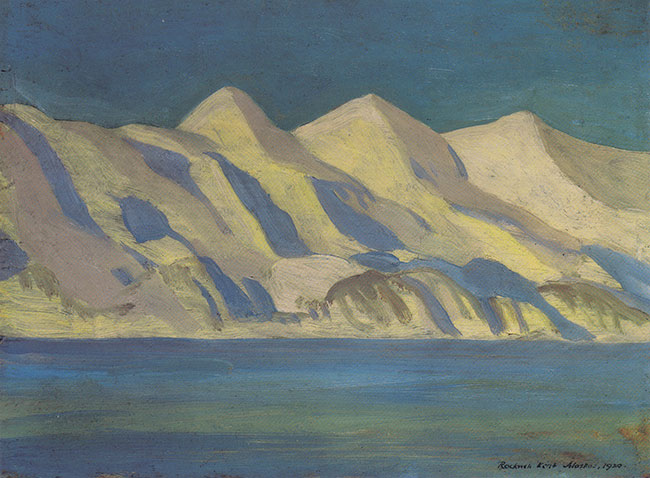

Brushstrokes 102: Signatures

Rockwell Kent’s signature was relatively basic. More often than not, through the late 1910s and early 1920s, the signature appeared with upper case first initials and lower case subsequent letters. Simple enough that a copyist could virtually reproduce the signature. Let’s compare Kent’s signature on his paintings Mt. Equinox, Winter (Art Institute of Chicago) and the Alaska Impression (fig. 13 and fig. 14) with the signatures on “Vermont Study” and “Adirondack Landscape.” (fig. 15 and fig. 16) Now let’s expand that comparison to include signatures that are seen on a composition of a city scene (fig. 17 and fig. 18), another of a farmer, with a horse, plowing a field (fig. 19 and fig. 20), and a mountainous winter landscape (fig. 21 and fig. 22), all by unknown artists: Varying signatures, like varying brushstrokes, that pull us further and further away from what we may have believed to be the work of Rockwell Kent (1882-1971).

Proclamations…

According to an essay in Antiques and Fine Art magazine (Rockwell Kent’s ‘Egypt’: Shadow & Light in Vermont, Summer 2012, p. 141), and in variant rewrites such as the Bennington Museum’s exhibition catalogue of the same name, and the museum’s current display label: “‘Vermont Study’ is undoubtedly the earliest oil painting that Kent conceived in Vermont and closely relates to the artist’s ‘impressions’ from Alaska, in terms of its physical characteristics, style, technique, and compositional strategies.”

When one closely examines the Alaska Impression that is discussed in these publications and label, you can see the “broad and narrow and abrupt, horizontal and vertical brushstrokes” that I mention above — when I speak about the Kent family painting of Mount Equinox. (fig. 23) You do not see the same brushstrokes in “Vermont Study.”

In Rockwell Kent: The Mythic and the Modern (Portland Museum of Art. 2005) the author states that “‘Vermont Study’ shares the same swelling landscape forms and rhythmic ordering of receding planes. It exemplifies how Kent reordered nature in imaginative ways.” For the reasons I illustrate above, the relationship between “Vermont Study” and Kent’s Vermont paintings entice comparison but do not definitively identify the former work with the latter. These are stylistic comparisons that, as we have read in the case of the Steele Savage drawing mentioned above, require reconsideration.

Coda

When I first saw “Vermont Study,” as well as the “Other Kents” that I discuss and/or illustrate, an alarm bell rang out. Perhaps, after 40 years of studying Rockwell Kent’s artwork, I have a visceral response to what I see: which takes over and informs what I cannot otherwise explain at the moment.

I can see why people associate some of the “Other Kents” to Rockwell Kent (1882-1971) but I find no compelling evidence to share their belief.

© Scott R. Ferris – May 2018

In Review: Blue Day

In Review: Blue Day

Blue Day first came to auction at Sotheby’s in December, 2003. It returned to the block, at Sotheby’s, in May, 2017.

An ardent celebrant of Life, Rockwell Kent traversed the world, frequently leaving his footprints in its harsh polar regions. His deep affection for the distant latitudes has its roots in the Nordic tale, The Saga of Burnt Njal, a prophetic tome brought to his attention by his mentor Abbott Thayer. Kent recounts, in his exhaustive autobiography It’s Me O Lord, that Burnt Njal “opened the gate upon that highway to the North which led at last to Greenland and Alaska” (Kent, p. 110). The artist’s early, prolonged stays in the remote communities of Monhegan Island, Maine and Brigus, Newfoundland further encouraged him to venture north, as well as to Tierra del Fuego in the Antarctic. Kent’s sojourns in the “wilderness — the only abiding place on earth of liberty” (Kent, Salamina, quoted in Scott R. Ferris, In the Presence of Light, 2003, p. xx) — were “the flight to freedom of a man who detests the petty quarrels and bitterness of the crowded world (Alaska Drawings by Rockwell Kent, New York, M. Knoedler & Co., 1919).

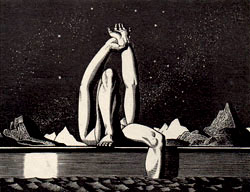

Rockwell Kent’s tales of his first trip to Greenland (1929) are told in his book, N by E. The artist’s graceless but newsworthy shipwreck upon the shores of Karajak Fjord initiated his historic three voyages to that largest of islands. His subsequent trips in 1931-32 and 1934-35 are retold in Salamina and Greenland Journal.

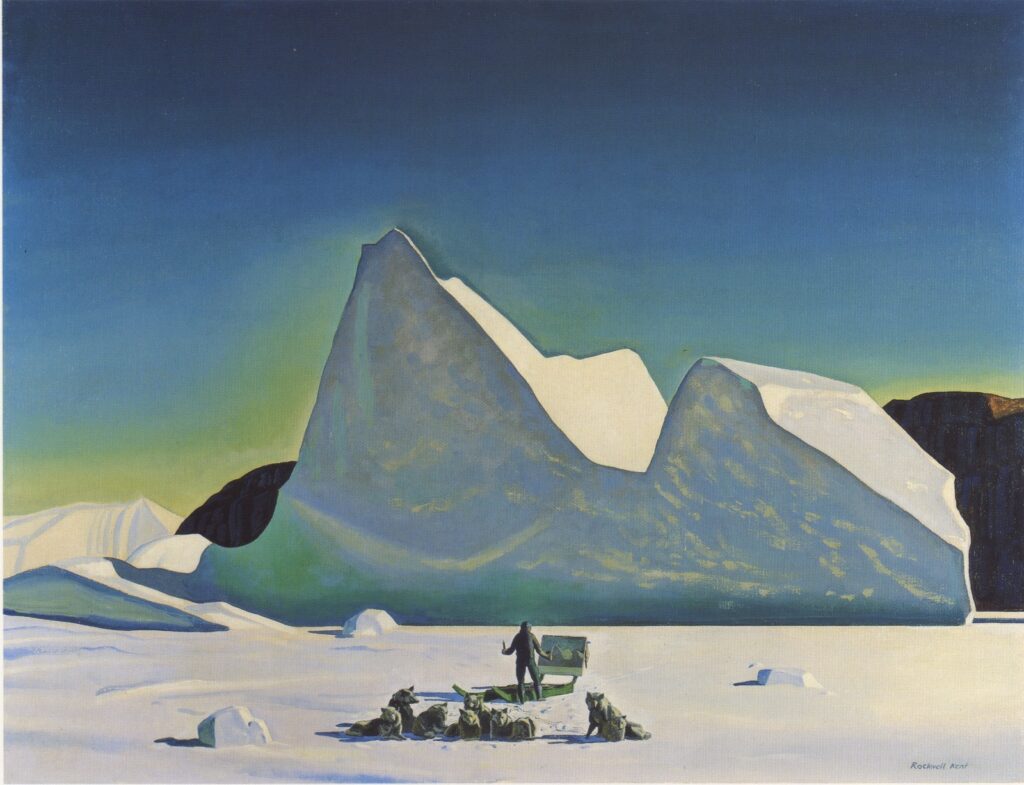

Many of the paintings that Kent created during his extended visits to Greenland typify the apogee of his artistic achievements. Blue Day, like his paintings Winter, Monhegan (Metropolitan Museum of Art), Toilers of the Sea (New Britain Museum of American Art), The Road Roller (The Phillips Collection) and Citadel (National Gallery of Art) share the pantheon of American Art with George Bellows’s Evening Swell (itself an homage to Kent’s Toilers of the Sea) and Edward Hopper’s Early Sunday Morning (Whitney Museum of American Art).

Arthur Lismer, a member of the Canadian “Group of Seven,” and no foreigner to the Arctic terrain, wrote that Kent “grasps the forms of earth and sky in a powerful summary and… feels the color and design fundamentally… he strives after the big rhythms creating order through the design of land, water and sky.” (The Art Gallery of Toronto, Grange Park Bulletin, April, 1934). Distinguished art critic Royal Cortissoz wrote that Kent “secures his pictorial balance in the first place by his massive treatment of nature in all her dignity and then by the power with which he defines a long flowing contour” (New York Herald Tribune, February 8, 1942).

Like Citadel and Gray Day, Kent created Blue Day from abstract forms — paint applied with dabs and brushstrokes of varying sizes, shapes and orientation — that float within flat, horizontal fields of color: techniques that would appear years later in the paintings of Clyfford Still, Mark Rothko and the Color Field painters.

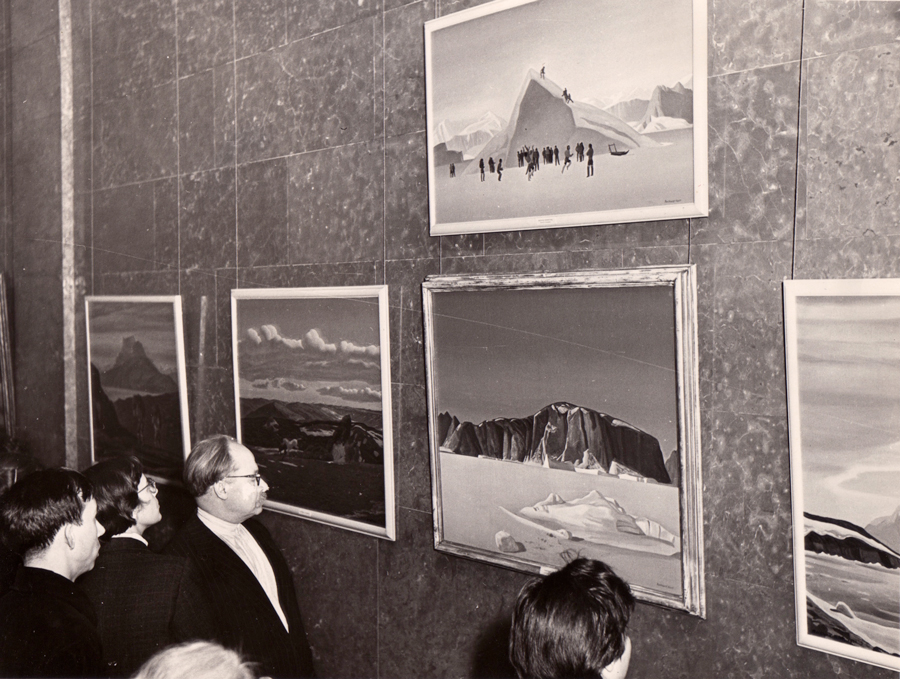

In September 1950, Robert McIntyre of Macbeth Gallery wrote to Rockwell Kent to inform him of a client’s interest in purchasing paintings by the artist. Inspired by the shared interest in Progressive politics, Joseph James (“J.J.” also known as Jim) Ryan, grandson of renowned financier Thomas Fortune Ryan, became the leading collector of Kent’s paintings. Before the end of September, he had purchased three of Kent’s canvases, one Irish and two Alaskan landscapes. In November, Ryan purchased another five paintings, including Citadel, Gray Day, and its companion composition, Blue Day. Not only is Blue Day one of the paintings Ryan selected from Kent’s oeuvre, this painting was also chosen to appear on the cover of his autobiography It’s Me O Lord. Ryan would acquire just over 30 oils in all, many of which, including Blue Day, along with 54 other oils and approximately 163 graphic works, was exhibited in five cities in the USSR from December 1957 through November 1958. The overwhelming positive response to Kent’s work was a leading factor in his decision to bequeath his personal collection to the Soviet people. Had J.J. Ryan not purchased Blue Day prior to the exhibition, there is reason to believe that it would have become one of the paintings that Kent gave to the Soviet Union in 1960.

- 1935-1937

- Oil on canvas mounted on plywood

- 34 x 44 1/2 inches

- Signed and dated lower left: Rockwell Kent 1935-7, and inscribed lower right ©

Provenance

- The artist

- Joseph James (“J.J.”) Ryan (via Macbeth Gallery)

- Peter Brady (nephew of J.J. Ryan)

- Private Collection in Massachusetts

- Collection of Richard Manoogian (via Sotheby’s)

- Collection of Deborah and Edward Shein

- Sotheby’s

Exhibited

- Washington, D.C., Gallery of Modern Masters, Greenland Paintings and Prints: Rockwell Kent, 1937, no. 17

- Dayton, Ohio, Dayton Art Institute, Paintings, Lithographs, Wood Cuts by Rockwell Kent, 1940;

- Houston, Texas, Meinhard-Taylor Galleries, Paintings, Lithographs, Wood Cuts by Rockwell Kent, 1940, no. 6

- New York, Wildenstein Galleries; Los Angeles, California, Stendahl Art Galleries; Stockton, California, The Haggin Museum; Beloit, Wisconsin, Theodore Lyman Wright Art Hall, Beloit College; Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, Carnegie Institute; Boston, Massachusetts, Boston Symphony Orchestra, Symphony Hall, Know and Defend America, 1942-43, no. 19

- Moscow, USSR, Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts; Leningrad, USSR, State Hermitage Museum; Kiev, USSR, Kiev Museum of Western and Eastern Art; Riga, USSR, State Museum of Fine Arts, Rockwell Kent: Paintings and Graphics, 1957-1958, no. 38

- Portland, Maine, Portland Museum of Art, Rockwell Kent: The Mythic and the Modern, 2005, no. 130

- Salem, Massachusetts, Peabody Essex Museum, To the Ends of the Earth: Painting the Polar Landscape, 2008-09

- Canton, New York, Brush Art Gallery, St. Lawrence University, The Once Most Popular American Artist, 2012

Literature

- Rockwell Kent, Rockwell Kent, New York, 1945, illustrated

- Rockwell Kent, It’s Me O Lord: The Autobiography of Rockwell Kent, New York, 1955, illustrated in color opposite p. 56, also illustrated in color on the dust jacket

- Jake Milgram Wien, Rockwell Kent: The Mythic and the Modern, Portland, Maine, 2005, illustrated p. 78

- Samuel Scott, Russell A. Potter, John Paul Caponigro, To the Ends of the Earth: Painting the Polar Landscape, Salem, Massachusetts, 2008, illustrated p. 4

© Scott R. Ferris

In Review: Frozen Falls (Alaska)/Ice Curtains

In Review: Frozen Falls (Alaska)/Ice Curtains

Frozen Falls (Alaska), also known as Ice Curtains, was offered by Christie’s, New York, in their 22 November 2016 American Art auction. It failed to sell.

- Ice Curtains [original title]

- Frozen Falls (Alaska) [Peter A. Juley & Son title]

- Frozen Fall (Frozen Fall/1962) – pencilled on masonite

- [“Emerald”: title referred to in Jake Milgram Wien’s article, “Origin Stories No. 4: Rockwell Kent Paintings in Focus,” Rockwell Kent Review, Volume XLI/2015-2016. The use of the title “Emerald,” as applied to this painting, is unsubstantiated.]

- Painted circa 1919 and 1952 (with alterations potentially occurring between these dates)

- Oil on canvas mounted on masonite

- 34″ x 28″ (86.4 x 71.1 cm)

- Signed lower right

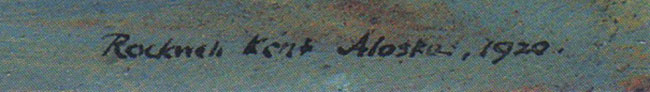

- [Original signature and annotation: “Rockwell Kent, Alaska, 1919.” Confirmed in Peter A. Juley & Son photo.]

- Labels on verso: “XII Esposizione Internazionale d’Arte/della Cittá di Venezia – 1920 1010” and “Merci Visitate/9057/Dogana Italiana.”

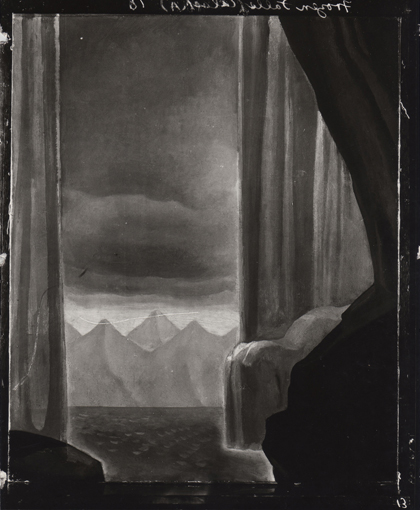

This painting, as it was originally conceived, was titled Ice Curtains (Alaska Paintings exhibition brochure). A photograph taken by Peter A. Juley & Son (New York), circa 1920, bears the handwritten title, Frozen Falls (Alaska). A third reference to a title was written on the verso, in pencil, “Frozen Fall.”

There are at least three paintings that are similar in appearance and similarly titled. As a result, it is virtually impossible to ascertain which among them were exhibited at any given time (that is, in their earlier history): The exception being when we have additional documentation — the title/composition relationship — Ice “Curtains” — in the Knoedler brochure; the labels for the Venice exhibition of 1920; the photograph of the painting at Frazers Stable Gallery exhibit.

EXHIBITIONS

(Known)

- M. Knoedler & Company, New York, Alaska Paintings of Rockwell Kent, March 1-12, 1920, no. 7

- Venice, Italy, “XII Esposizione Internazionale d’Arte/della Cittá di Venezia” (Twelfth International Exposition, Venice) April 15-October 31, 1920

- Frazers Stable Gallery, 1910 S Street, NW, DC, December 20, 1977-January 7, 1978

OTHER POSSIBLE EXHIBITIONS

(For “Frozen Falls)

- Carnegie Institute, Pittsburgh, Rockwell Kent: Exhibition of Paintings [retrospective], January – February, 1924 no. 19 (As Frozen Fall)

- Arts Club Exhibitions at the Art Institute of Chicago, Exhibition of Paintings by Rockwell Kent, March – April, 1924, no 14 (As Frozen Fall)

- Wildenstein Galleries, New York, Retrospective Exhibition of the Paintings and Drawings of Rockwell Kent, April-May, 1924, no. 21 (As Frozen Fall)

LITERATURE

(Selected)

- Henry McBride, “Paintings by Rockwell Kent on View at Knoedler’s–In Other Galleries,” New York Sun, March 21, 1920

- Forbes Watson, “Rockwell Kent, Incorporated,” Arts & Decoration, March 25, 1920

- “The Alaska Paintings of Rockwell Kent,” New York Times [author unknown], March 7, 1920

- Benjamin Forgey, “Rockwell Kent: In His Paintings, a Paradox Recalled,” Washington Star, December 20, 1977. “Frozen Fall” illustrated

- Jake Milgram Wien, “Origin Stories No. 4: Rockwell Kent Paintings in Focus,” Rockwell Kent Review, Volume XLI/2015-2016. (Thought to be another painting titled Emerald)

BACKGROUND

Rockwell Kent, with his son Rockwell (who turned 9 while in Alaska), “found Fox Island on Sunday, August twenty-fifth, 1918, and left there finally on the seventeenth of the following March.” From this sojourn the artist wrote his tome, Wilderness: A Journal of Quiet Adventure in Alaska (G. P. Putnam’s Sons, New York, 1920) and created dozens of paintings and drawings, and endeavored to make some relief prints. Two acclaimed exhibitions followed the artist’s return: Alaska Drawings by Rockwell Kent (M. Knoedler & Co., New York, April, 1919) and The Alaska Paintings of Rockwell Kent (M. Knoedler & Company, March, 1920

FROZEN FALLS

(Its Origins)

Frozen Falls (Alaska) was originally titled Ice Curtains before the artist reworked the painting to its current presentation. The former title was written on a photograph taken by the fine arts photographers Peter A. Juley & Son, in New York. The title Ice Curtains is documented in the brochure of Kent’s first exhibition of this work, in 1920, at M. Knoedler & Company.

When one compares Frozen Falls with the photograph of Ice Curtains taken by Juley, you can see the pentimenti of the three dominant mountain peaks, as well as, the vertical strip on the left that once was the second waterfall (or a division of the larger waterfall to the right). This fits Kent’s statement that he was “almost beneath a frozen waterfall” when he painted the work. (Kent, journal entry for February 14, 1919, as quoted in Wilderness, pages 184 and 187) The form of the waterfall on the right, as well as its supporting rocky cliff, is virtually untouched.

In Jake Wien’s article in the Rockwell Kent Review (as noted above), he argues that Frozen Fall, Alaska, at Plattsburgh State Art Museum, was originally Ice Curtains. I argue that this is not the case.

In addition to the similarities between the Christie’s painting [The Oak Ridge Collection] and Ice Curtains, that I have mentioned, it is important to note the following significant difference between the Plattsburgh painting and Ice Curtains. In the lower left corner of the Plattsburgh painting, in the pentimenti, one can still see the remnants of a jagged, two- or three-pronged rocky outcrop, that is not present in the Juley photo of Ice Curtains. Therefore, the Plattsburgh painting could not have originally been Ice Curtains, as Mr. Wien suggests. (This also supports my theory that there are probably more than the three “Frozen Water Fall” paintings that I discuss in this essay.)

The same similarities between Ice Curtains and Frozen Falls — the virtually unaltered waterfall to the right of the composition–exist between Sun and Ice and Frozen Waterfall, Alaska at the Art Gallery of Hamilton (which helps to confirm its origins). Presumably we will one day find an image of the Plattsburgh painting in it’s original state.

One other note regarding these three paintings: Due to their stylistic similarities it would be fair to say that all three were most likely reworked by the artist around the same time — early 1950s, if not before: though they could also have been marginally touched up at any time during the 1950s-60s. This also contrasts with Mr. Wien’s theory on the development of these paintings.

In Kent’s book, Wilderness, he describes and illustrates the terrain around which this painting was conceived. However, one’s interpretation of the terrain is obfuscated by the artist’s later alterations to the painting. Kent notes that he painted at both geographical points (at the tips) of Northwest Harbour. From the southern point of Northwest Harbour, at a rocky promontory, — his relationship to a frozen waterfall — it is at a spot from which it would be virtually impossible to see the tip of Bear Glacier. Kent wrote: “This afternoon I painted at the northern end of the beach almost beneath a frozen waterfall, an emerald of huge size and wonderful form.” (Kent, journal entry for February 14, 1919) It is therefore possible that when Kent painted Frozen Falls, he was looking to the northwest. Kent’s sketches on pages 134 and 162 (looking southwest) and on page 169 (illustrating “Frozen Fall,” presumably to the northwest) also suggests that he painted at the two harbor points, thus, looking in two different directions. Furthermore, Kent states in his February 20th journal entry that he painted at the second point, the rocky promontory “between the two coves of the island” — there are two coves on Fox Island: Sunny and what Kent called Northwest Harbour. And, inscribed in the map that serves as frontend papers to Wilderness, Kent says, “At low tide one can climb around this head and pass from one bay to the other.”

RELATED PAINTINGS

As I previously mentioned, Kent’s painting Bear Glacier was painted at the base of the promontory between Sunny Cove and Northwest Harbour. Another composition that fits this description is Alaska (Art Institute of Chicago), though in this painting the prolonged rocky base is very abrupt, as it juts out into the water; and, on the opposite shore, a lower, timbered frontal range is dominated by a towering mountain peak in the distance. (This latter painting is signed, inscribed “Alaska,” and dated 1919-27 — a reference to its inclusion in the 1927 Wildenstein exhibition.) Because of the sharp differences between the Bear Glacier and Alaska paintings, it is possible that they do not represent the same geographical location.

Nevertheless, they do inspire us to consider the location/s of the various “Frozen Falls” paintings. Perhaps Bear Glacier even more so because of the fact that its cliff dons a frozen waterfall that is not unlike that which we see in Frozen Falls. And, in considering the location/s of the “Frozen Falls” works, we can begin to understand the development of these artworks, in particular — how they transformed from simplified, almost primitive landscapes into the more elaborately detailed paintings that they are today.

Before we close on comparative works, let’s consider three more paintings. One painting that appears to depict the same location as Alaska (AIC) is a composition referred to as “Frozen Lake” (Brady Collection) — by way of pencil inscriptions on the verso (one, by Peter Brady, that may have no basis on fact; the author of the second inscription needs to be identified). This painting also appears to illustrate Callisto Point, but with the front range that I mention above. Another painting, simply known as Alaska (Edwards Collection), may have been painted from a higher elevation, possibly above Sunny Cove: it appears to depict Bear Glacier as it protrudes into Bulldog Cove, with a slightly downward view. Alaska, from the Edwards Collection, also reminds us of the many paintings of Resurrection Bay (Portland Museum of Art, Frye Art Museum, etc.).

The small “impression,” “In Shadow of the Cliff,” that is in the collection of the Alaska State Museum (Juneau), brings up another point for discussion: authorship. This latter painting is very crude in its execution — appearing to be by another hand; though it has good provenance — Richard Larcada, One Art Service. This work shows a similar scene, that of a rocky cliff to the left, a small bay, opening into what we assume to be Resurrection Bay, and a mountain range in the distance. As the proposed painting title, “Frozen Lake” (origin as yet unknown), suggests, and as Kent’s map depictions define, there is a lake on Fox Island, around which the artist could have rendered some of these compositions.

WORKS IN A SERIES

Frozen Falls is one in a series of paintings that depict the frozen waterfall on the northern point of Northwest Harbour, on Fox Island. Two other works included in this series are what are known today as Frozen Waterfall, Alaska (originally known as Sun and Ice as well as Sun and Sea. Art Gallery of Hamilton) and Frozen Fall, Alaska (Plattsburgh State Art Museum).

The serial compositions of frozen waterfalls on Fox Island are only one of several series that Kent created throughout his career. Additional series included multiple depictions of the headlands on Monhegan Island, Maine, the view from Mount Greylock in the Berkshires of Massachusetts, and views of Mount Equinox in Vermont and Whiteface Mountain in the Adirondacks of New York. One can assume from these repeat visits to the same location that Kent intended to capture varying momentary effects. Indeed, as he said when speaking about his “Alaska Impressions” paintings: they are “exceptionally vivid impressions of momentary effects.”

CLOSING REMARKS

Period Reviewers’ Impressions of Frozen Falls (Ice Curtains)

A reviewer for the New York Times (March 7, 1920) wrote: “One of his titles is ‘Ice Curtains,’ and the drapings [sic] of frozen color associate themselves in one’s mind with the drama of the Vikings. Only a race of giants could people such wilderness on a scale appropriate to the setting.” And in a review by Henry McBride of the New York Sun (March 21, 1920) he opined: “The far north is gaunt and bare. The artist is more emphatic upon that point than any other traveller who got as far north as Resurrection Bay, but if I, as a critic, stand shoulder to shoulder with [other viewers] for a moment, it is not so much because of Mr. Kent’s drastic simplifications as it is for the true effects of light that he dispenses and his genuine instincts for form and color.”

As with many of Kent’s paintings, further research is required.

© Scott R. Ferris

In Review: Gray Day

In Review: Gray Day

The following two writings were drafts for my essay for Sotheby’s catalogue entry for Rockwell Kent’s painting, Gray Day (see Sotheby’s “American Art,” New York, 21 November 2016, #25, pp. 46-51). A link is hereby provided for the actual publication: www.sothebys.com. I also provided Sotheby’s with the basic catalogue data.

The unprecedented assembling of numerous Rockwell Kents, for sale, at Sotheby’s, Christie’s, and the American Art Fair, in November 2016, undoubtedly had its effect on the Kent sales. The four paintings at auction–Gray Day, Icebergs (Greenland), Frozen Falls (a.k.a. Ice Curtains) and Alaskan Impression–reaped mixed results. The three prominent paintings offered by Manhattan galleries – Sledging, the descriptively titled “Greenland Mountains and Sea,” and Sunday Evening, Greenland – went unsold (to my knowledge). Alaskan Impression broke public sales records for an artwork of that size. Frozen Falls was passed: perhaps because of the later, total reworking by the artist. Icebergs established a new second highest public sale record; and Gray Day became the new public sale record holder: both of which topped Polar Expedition, that was sold by Heritage Auctions just a few years ago.

For just reasons Sotheby’s went all out in promoting Gray Day–numerous pages were devoted to the work within their catalogue, the painting appeared on the back cover of their main catalogue, as well as, in their mini-catalogue; the canvas was previewed on their 10th floor, with other (well established) “modernist” works; the painting hung above the auctioneer during the sale; in addition to other endeavors by the auction house. The reason for this outpouring of promotion was to point out the fact that there is a “quality tier” of artwork by Kent (as with all artists); and Gray Day, like Citadel (unfortunately buried in the collection at the National Gallery in DC), Blue Day, Toilers of the Sea (New Britain Museum of American Art), Winter, Monhegan (Metropolitan Museum of Art), etc., exemplifies the best in Kent: certainly on par with the best of Edward Hopper, Marsden Hartley, and George Bellows, among others. Gray Day was, simply put, the most important Rockwell Kent painting that was offered for sale in November: a point, I am afraid, that may have been lost on the buying public.

The sale at Sotheby’s, as well as the November sale at Christie’s, was reviewed by Maine Antique Digest (February, 2017) in the articles “Sotheby’s American Art” (pp. 13-14-D) and “‘Hands Up!’ Goes Way Up” (pp. 26-28-E). A review of the American Art Fair sales, also penned by Julie Schlenger Adell, and which also included artwork by Kent, can be found on pp. 22-25A.

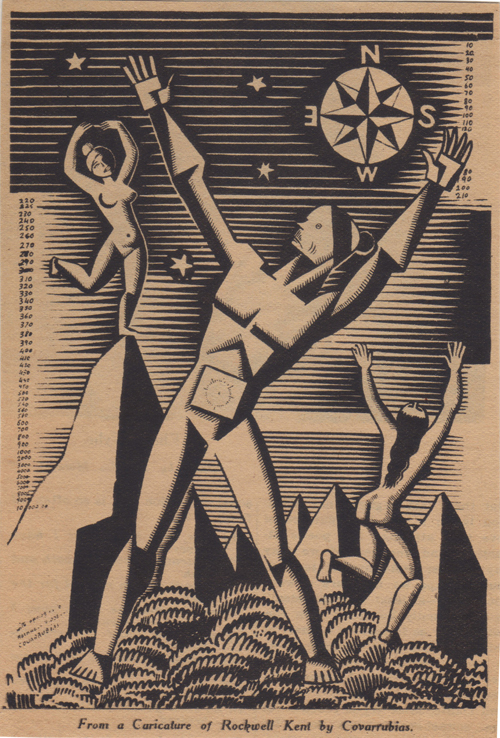

GRAY DAY

Throughout the 1930s Rockwell Kent’s popularity had reached such heights that The New Yorker wrote: “that day will mark a precedent, which brings no news of Rockwell Kent.” (November 20, 1937) And artists for Ken, Americana, Ballyhoo and other publications, caricatured Kent for his renowned wanderlust. Miguel Covarrubias played on Kent’s restless endeavors to attain greater heights (publication unknown), whereas Alan Dunn played on everyman’s desire to acquire “a new Rockwell Kent,” as seen in The New Yorker (11/4/1933). With Newfoundland, Alaska, Tierra del Fuego, and now Greenland in his travelogues, Kent had become synonymous with the adventurous spirit; and while paintings like Gray Day are records of the artist’s journeys, they are, above all, an extension of the artist himself.

In Greenland, surrounded by vast open spaces, polar light, endless horizons and barren terrain, Kent had found his ideal motif. His paintings Gray Day, Blue Day, Citadel, and North, among others, represent the consummation between artist and subject that defines his most revered work. Though other modernists, including Marsden Hartley, Georgia O’Keeffe, Arthur Dove and Edward Hopper, were visually reflecting on nature throughout their careers, the transcendent landscape had become Kent’s most distinctive theme.

Kent’s sojourns to the “edge of the world where infinite space begins” reinforced his belief that “it is the ultimate which concerns me, and all physical, all material things are but an expression of it.” (Alaska Drawings by Rockwell Kent, M. Knoedler & Company, New York, 1919, n.p.). This continuity of thought was expressed again nearly twenty years later when he said that “speech at its highest art–its metaphors and symbols, its rhythms and harmonies, its moods, its forms, its being–is derived by man from his environment.” (Kent, Salamina, 1935, p. 56) In Gray Day Kent spoke of his communion with Nature in a modernist language that blurred the line between academic illusionism and abstraction.

Other artists who traveled this middle passage included the organic abstractionist Arthur Dove, who exclaimed that “there is no such thing as abstraction” (Arthur Dove. “Notes of Arthur G. Dove.” Dove Exhibition. 1929); and Georgia O’Keeffe, who exercised subjective realism to educe the essence of a subject. Wassily Kandinsky, a German painter solidly of the abstract camp, and of some influence to artists such as Marsden Hartley, proposed that “with the artistic reduced to a minimum, the soul of the object can be heard at its strongest through its shell because tasteful outer beauty can no longer be a distraction.” (Donald Kuspit. “Concerning the Spiritual in Contemporary Art.” The Spiritual in Art: Abstract Painting 1890 – 1985. p. 314). In Gray Day Kent builds his representational imagery of the mountains of Kekertarssuak Island out of what appears to be random dabs and brushstrokes of varying sizes, shapes and orientation, floating within flat, horizontal fields of color–blues, magentas and raw umber: that would be painted by artists Clyfford Still, Mark Rothko and Adolph Gottlieb in the decades to come.

While on his solitary journeys by dog sled throughout western Greenland, Kent heard the sounds of the wind sweeping across the ice packed fjords, the barking of his dogs, the scraping of the rails of his sled on the terrain, and the soul of the landscape. His were the ears of a pantheist–one who sees the creation as God, as opposed to a theist who sees God as the creator. Kent defined his belief system when he stated: “God had become to me the symbol of the life force of our world and universe; a name for the immense unknown. Imponderable, yet immanent in man, in beasts… in the earth, sun, moon and stars. It––I choose the impersonal pronoun as alone consistent with my faith––It was to me a force as un-moral as such manifestations of itself as storms or earthquakes, and for that very reason greatly to be feared. It was as un-moral and impersonal and splendid as its sunset’s light on land and sea––and for that reason to be reverenced. I feared and reverenced god. In fear and reverence I painted”… Gray Day. (Kent, It’s Me O Lord, 1955, p. 138)

Rockwell Kent was as roughly hewn from the proverbial American maple tree as were his spiritual antecedents Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau and Walt Whitman. Thomas Cole’s conveyance of the “voyage of life” was a path similarly taken by Kent though with the harder edge of Winslow Homer and the spirit of Mother Nature. William Merritt Chase and Kenneth Hayes Miller helped the younger artist develop his sense of design and technical aptitude but it was Robert Henri and Abbott Handerson Thayer who instilled Kent with the belief in “art for Life’s sake”; and Kent specifically credits Thayer for introducing him to the Nordic saga, Burnt Nyal, which he said “opened the gate upon that highway to the North which led at last to Greenland and Alaska.” (Kent, It’s Me O Lord, p. 110). (Kent met, and eventually married, Thayer’s niece, Kathleen Whiting, whom he met at the elder’s home).

Throughout Kent’s adventurous artistic career, he had the support of several patrons–the art dealer Charles Daniel, and noted collectors Ferdinand Howald and Duncan Phillips–which enabled him to experience far away lands. In 1950 he met a new patron, Joseph James (J.J.) Ryan: the grandson of financier Thomas Fortune Ryan.

In a letter to Robert McIntyre, of Macbeth Gallery, –who served to introduce the artist and collector– Kent stated: “Gray Day, as I have told you, is in my judgment one of my very finest things” (November 9, 1950). And Gray Day, like Citadel, North, Blue Day (which also served as the dust jacket illustration), and May, North Greenland, all from Ryan’s collection, were chosen as full page color illustrations in Kent’s autobiography, It’s Me O Lord (Dodd, Mead and Co., New York, 1955). Ryan, like Duncan Phillips decades before him, essentially had his choice of paintings: in this case, before the artist gave the bulk of his personal collection to the Soviet Union (1960). Ryan ultimately came to acquire over thirty oils and numerous works on paper for his collection.

Fittingly, one hundred years later, Rockwell Kent was rejoined with his colleagues–Hartley, John Marin, Dove, O’Keeffe, Stuart Davis–when Gray Day, Blue Day, and Citadel (now at the National Gallery), descended from Ryan, through his family, to the Shein Collection.

GRAY DAY: FROM THE FIRST DRAFT

Kent’s work gives the impression of a world beyond the human circle. These whites, pale greens, blues and yellows, these naked brown rocks and the cold green water–in the midst of our busy life they act as a corrective. They restore our sense of proportion regarding man and universe, they teach us that there really is something ‘beyond’ our petty affairs. … Over his work there hovers the great silent question that is the birthright of all significant art.

Washington Post. Gallery of Modern Masters, Washington, DC, exhibition review. Oct. 31, 1937.

Few other American artist since Frederick Church and William Bradford would expose themselves to such hardships in exchange for the exhilaration and inspiration nature offered. From Kent’s window on Igdlorssuit he “came to feel–as though for the first time in [his] life–the beauty of the world!” Living, virtually outdoors, was “far profounder a devotion… than any Godward posturing of conscious worshippers! There,” in Greenland,”was God’s countenance itself, its light, its majesty of form, its power of life and death.” (Rockwell Kent as quoted by Scott R. Ferris in his “Foreword” to Salamina. Wesleyan University Press, 2003. p. XX.)

In William Murrell’s lengthy review of the 1911 Independent’s exhibition, –”The Exhibition of Independent Artists”–he acknowledged the division of aesthetic camps that would formally raise its head with the Armory Show two years later. What he could not anticipate, or perhaps reconcile, was the interweaving of philosophies and methodologies. From his 1911 perspective, he saw that the “Post Impressionist,” or “Neo-Primitives” (as he also referred to them), –in this case he was specifying four of the twelve exhibitors: Marsden Hartley, Alfred Mauer, Maurice Prendergast and John Marin–aimed to “give expression to the emotion caused by the object and not an impression of the object itself.” Whereas of Kent’s paintings, he considered them a “sturdy rendering of the grandeur and attraction of the big, open spaces.” As we look at these predominantly nature-based artworks in hindsight, dividing each into abstract or realistic categories diverts us away from the heart of the matter: the spirit of the subject.

Arthur Dove and Wassily Kandinsky reinforced this notion in similar ways. Dove exclaimed, “there is no such thing as abstraction” (Dove. “Notes of Arthur G. Dove.” Dove Exhibition. 1929), thus steering a “middle course between academic illusionism and modernist abstraction” (Kevin Muller. “Spirit of the Sea.” Masterworks of American Painting at the De Young. pp. 323-324). Kandinsky was more direct when he stated: “with the artistic reduced to a minimum, the soul of the object can be heard at its strongest through its shell because tasteful outer beauty can no longer be a distraction” (Donald Kuspit. “Concerning the Spiritual in Contemporary Art.” The Spiritual in Art: Abstract Painting 1890 – 1985. p. 314). Similarly, Kent proclaimed that “it is the ultimate which concerns me, and all physical, all material things are but an expression of it.” (Kent. Alaska Drawings of Rockwell Kent).

Critics often cited the artist’s bravura brushwork, his propensity to reduce and model compositional elements, and his strong, defining contours: yet, they failed to see Kent’s kinship with his broader community of contemporaries. It seems that many of the critics were as staunchly committed to labeling him as a pure realist as the artist was himself.

By Kent’s third sojourn to Greenland, –1934-1935–his painting technique had evolved from applying thick, rapidly applied brushstrokes, which shimmered light from the surface, to smooth, flatly painted color areas, with simplified elements, that radiated from within. (with Gray Day he was well on his way to reversing the source of light in his compositions: a process that reached its culmination by the 1950s.) In essence, Gray Day, and paintings like it, were precursors to the compositions developed by the Color Field painters (Mark Rothko’s White and Greens in Blue, for example). Kent’s paintings Calm (Tierra del Fuego) and April Ice (Greenland) are clear examples of this reductive approach.

Also of note is how these paintings were constructed. In compositions such as Gray Day and Citadel, the basic technical structure belies the realistic results. Upon close inspection, the compositional elements in these paintings are born out of what appear to be randomly placed brushstrokes of irregular form and size. They are in themselves abstract compositions, precursors of the finished canvases of Franz Kline and Clyfford Still. If you were to examine these paintings by Kent up close, focusing on how the artist constructed the mountains, –their raw, jagged forms–they might appear to be by the same hand as the oil on canvas PH-858 of 1972 by Still. Now slowly step away from the painting. In doing so you will see that these abstract constructs take on a more representational form, that of Kent’s most prominent muse, the mountain.

Now we have come full circle. Whereas Arthur Dove once suggested that “there is no such thing as abstraction,” Kent could have comparably stated, “there is no such thing as realism.” Both artists employed reductionist techniques, empowered by their spiritual relationships with Nature. At their finest, the works of both artists are modernist interpretations of the universe around us.

© Scott R. Ferris

In Review: Rockwell Kent in Newfoundland

In Review: Rockwell Kent in Newfoundland

A series of programs and an exhibition hosted by the Landfall Trust in partnership with The Rooms Provincial Art Gallery, held in St. John’s and Brigus, Newfoundland, May 30-September 21, 2014.

POINTED NORTH

Rockwell Kent in Newfoundland & Labrador

Exhibition curated by Caroline Stone. Associated publication: Vital Passage: The Newfoundland Epic of Rockwell Kent, with a catalogue raisonné of Kent’s Newfoundland works by Jake Milgram Wien, and a record of the 2014 exhibition by Caroline Stone.

Loneliness is what I want and what I came here for. Fortunately I… am literally carried in my work into a broader — more loving — universe that is as real to me as life itself. This has become my process. I do literally transport myself into the land that with my own pigments I create; painting has become for me the act of populating the realm that I build and that appears to me so splendid… I must confess to you that I am coming to realize and to believe, that I have a distinct spiritual message that is utterly different from anyones and is moreover well worth while.

Rockwell Kent to Charles Daniel, January 8th, 1915

INTRODUCTION

Throughout the middle months of 2014, Landfall Trust, in partnership with The Rooms, hosted a series of events — an exhibition, lectures, armchair discussions, a film — commemorating the centennial of artist Rockwell Kent’s stay in Newfoundland. Based on Kent’s positive experience in Newfoundland in 1910 he returned in 1914 (shortly thereafter followed by his wife and children) with the idea of starting an art school. (Kent had successfully conducted a school on Monhegan Island, Maine in 1910, and attempted another in Richmond, New Hampshire the following year.)

In short: Kent was able to create several paintings and drawings but his school never got off the ground; and, due in part to Kent’s “own past misdeeds,” as he referred to them in his book, After Long Years (Asgaard Press. 1968. p. 15) and Newfoundlanders’ “past injuries,” as Premier Joseph Smallwood was quoted (Kent, p. 12) the Kent family left Newfoundland, in 1915, under less than amicable terms. (Mutual animosity arose when Kent was suspected of being a spy for the Germans, at the outset of what we now refer to as World War I.) Fast forward to 1968, Premier Smallwood invited Kent and his wife Sally, to return to Newfoundland so that they could “show her regard” for Kent.

AN EXHIBITION AND PROGRAM WERE FORMED

Held at The Rooms in St. John’s, and at various locations in Brigus.

According to curator Caroline Stone, in her record of the exhibition (pp.76-77): “what began as a very focused exhibition idea expanded to present Kent at several significant periods of his long career.” The exhibition, as she further clarified, was organized in “two principal sections”: the first being made up of Kent’s Newfoundland related artwork — drawings, paintings prints; the second, work pertaining to Kent, “which [has] a connection to Newfoundland and Labrador through ownership.” “A small bonus,” she continued, was “the addition of several historical and contemporary works by other artists that have a link to Kent.” (A precedent setting, traveling Kent-Newfoundland exhibition and catalogue — Rockwell Kent: The Newfoundland Work — had been organized by Gemey Kelly in 1987 for the Dalhousie Art Gallery, Dalhousie University, Halifax, Nova Scotia.)

Regarding the development of the centennial programs, Milly Brown — director of programs for Landfall Trust — said, in an email, “[We] just put together a string from various contacts we had and it all fell in place.” Sixteen individuals were invited to participate to discuss topics such as “Influences of Brigus and Newfoundland on Kent’s Art,” “Kent’s Life in Newfoundland,” “The House of Dread” (a Newfoundland painting by Kent), and Kent in fictional writings. [Neither Gemey Kelly (to my knowledge) nor this author were invited to participate.]

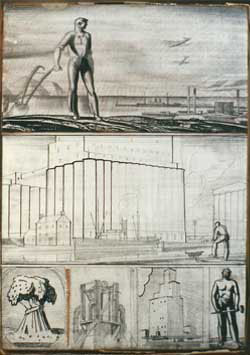

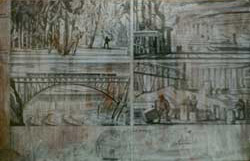

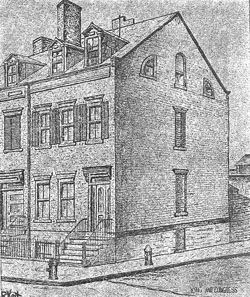

OBSERVATIONS IN AND OUT OF THE GALLERY

Of the few paintings that highlighted the exhibition, a 24 x 96 inches (over all) oil on board The Rooms refers to as “Mural” — “undated (may be inspired by Alaska or Greenland)” — was certainly the largest. This work, as I had mentioned in an extensive appraisal that I wrote for ADAC (Art Dealers Association of Canada) and The Rooms in 2007, represents half of a diptych. Kent created the diptych as two back-to-back panels, mounted on stacks of hay on the back of his Asgaard Farm pick-up truck. The diptych was used as a float in a local Adirondack parade, to advertise his Asgaard Dairy business (fig. 1 and fig. 2). The concept for the composition of this panel has antecedents in works such as the title pages for Kent’s 1930 book, N by E, and his packing label for Rockwellkentiana (1933) — both of which boast Greenland motifs. (The mate to this painting had been owned, at various times, by J. Stewart Gordon and Richard York Gallery, and auctioned by Doyle, of New York.)

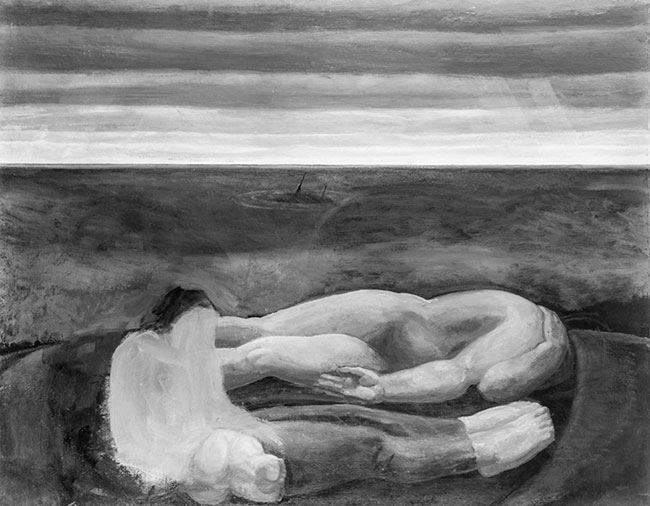

Another painting on display was Newfoundland Dirge (a.k.a. Women). This painting, like others that Kent had kept at his studio over an extended period of time, was subject to the artist’s recreative whims. In this case, as documented in Ms. Kelly’s Dalhousie Gallery exhibition catalogue (p. 47), the artist painted over areas of the composition: virtually obliterating the reclining female figure and the majority of the depicted baby (fig. 3). Mr. Wien [heretofore, “the author”] had the overpaint removed and in his exhibition catalogue says that this painting was conserved.

(There are other occasions on record, of Kent’s artwork being altered posthumously. For example: As I mentioned in my In Review (2005) on the revised edition of Dan Burne Jones’s, The Prints of Rockwell Kent: A Catalogue Raisonné (Alan Wofsy Fine Arts. 2002), artist/printer Letterio Calapai “restored” a wood engraving and “finished” another — works that Kent had abandoned; And, at least one of Kent’s reverse paintings on glass was “completed” well after the artist’s death. [More on these in a future essay.])

The author also asserts, when referring to other compositions that the artist was reworking, that Kent “thwarted an accurate reading of the Newfoundland paintings…” that the artist “disavowed the avant-garde Symbolist spirit animating the Newfoundland Epic…” and that the artist’s “revisions” were intended to “diminish their sense of cosmic mystery.” As if to trump the artist the author boldly states that Newfoundland Dirge was “expertly conserved in New York and returned to its original state” (fig. 4). (The author refers to one other painting that Kent had reworked — The Shepherd-cat. no. 7 p. 35 — as “later revised.” True.)

Late in life, as documented in his autobiography, It’s Me O Lord (Dodd, Mead & Co. 1955. pp. 288-290), Kent tells us that the tragedy in Newfoundland, for he and his family, was “our hidden but prevailing misery.” Of tremendous emotional weight was the tragic loss of life of the seal hunters aboard the S.S. Southern Cross and S.S. Newfoundland — presented in Kent’s account, “A Tragedy of Newfoundland” (1914); the onset of World War I; and the consequences of his own “misdeeds” — his backfired pranks, and the wartime suspicions he inspired. As a consequence, the brooding atmosphere, heightened by long periods of darkness, effected the end results of the artist’s achievements.

In hindsight, Kent made it clear, through his writings, that he thought lesser of some of the artwork that he created during this period. Perhaps, as a result of his disenchantment, Kent found more value in these canvases as the base for other compositions. Perhaps, as in the manner of canceling a wood engraving block, — which one would deface — he was canceling these compositions. Regardless, the decision to create and then alter was the artist’s to make.

THE CATALOGUING PROCEDURE

It is important to note that the provenance of Kent’s artwork is often difficult to follow, due, in part, to his varying methods of “marketing” — outright purchases, trades, gifts, loans. What makes matters worse for Kent scholars is the artist’s common practice of retitling his artwork. The author fell into these traps: following are some examples.

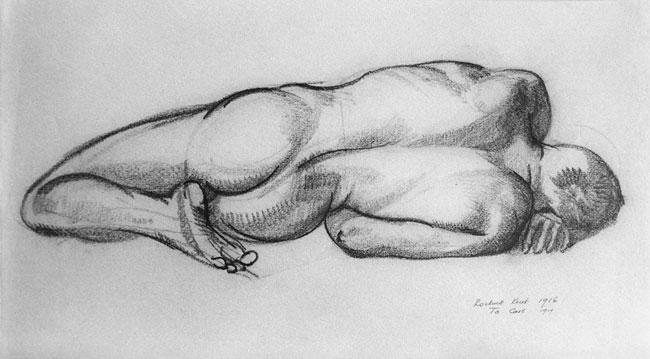

In his catalogue entry for Portrait of a Child, the author makes no mention of the paintings association with Kent’s friend, the composer, Carl Ruggles. As I note in my book, Rockwell Kent’s Forgotten Landscapes (Down East Books. 1998. p. 78), the artist inscribed — lower right; just below the baby’s head — “To Carl Ruggles From Rockwell Kent.” If one looks closely at the illustration of “Portrait” in Kent’s book, Rockwellkentiana (Harcourt Brace & Co. 1933), you can just make out that inscription. In the course of reworking this painting Kent covered over the inscription.

Also with regards to provenance, the author does not address the purported one time ownership of Kent’s painting, Bones of Ships, by Mrs. Harry Payne Whitney. In November, 1921, American Art News announced that Whitney purchased seven American paintings for the purpose of giving them to American museums: the article states that she acquired Bones of Ships. An interesting twist to this provenance is that in 1929, Kent traded, with collector Duncan Phillips, “Bones,” for a work referred to as “Bonson, Maritime Alps” [etc.] — a painting Phillips had acquired shortly before. Questions of provenance, such as these, should be resolved in a catalogue raisonné.

Regarding titles: the author mentions only a few of the variant titles that the artist and others applied to his paintings: Let’s take Portrait of a Child, for example. In “Forgotten Landscapes” (p. 92), I listed six of these titles: some appear in Kent’s documents; others in publications that he had a hand in producing.

Kent did not apply titles to many of his works: sometimes giving that task to a paintings “adoptive parents” — he often referred to his paintings as his children; and, often, without acknowledging a reason, he applied more than one title to a work of art. Without the benefit of knowing all variations, one could easily lose track of a paintings provenance, exhibition history, even which painting is being addressed.

ON INTERPRETATION AND PARAMETERS

There is no license on interpretation. There are parameters on a catalogue raisonné.

The author argues for a direct relationship between Kent’s To The Stars and his Newfoundland work (“To the Stars” — Andreieff. Also spelled Andreyev, etc. 1937). He says that early in Kent’s time in Brigus, Kent and artist Kenneth Hayes Miller communicated about Andreyev’s drama; and mention was made of a topically related sketch that Kent rendered.

Without a doubt there is a literary connection. And as you read Kent’s writings, you discover numerous influential literary antecedents that the artist carried with him, and evoked in his work, throughout his life. (Beyond Andreyev’s To the Stars, Goethe’s Wilhelm Meister, the Bible, and Darwin’s On the Origin of Species, come to mind.)

So what are the parameters that the author set when he included artwork under the Newfoundland umbrella? Is it work that was actually begun in Newfoundland — in 1910 or 1914-1915; work that was begun at an earlier time but completed during this period; work that was conceived during this period but finished much later? Do works created outside of the time Kent actually spent in Newfoundland have to bear characteristics of the locale or might they simply possess conceptual roots?

If To the Stars, Burial of a Young Man (ca. 1908-1911), and The Seiners (ca. 1910-1913) can be included in this catalogue raisonné, then why exclude A Mother and Her Sons (Motherhood, etc. 1913)? The author included this painting in his Rockwell Kent: The Mythic and the Modern exhibition catalogue (Portland Museum of Art. 2005), suggesting it “previewed the psychological dislocations evident in his works from Newfoundland” (Wien. “Mythic and the Modern,” p. 36). And, this painting possesses compositional as well as palette similarities to the work begun in Newfoundland. And, chronologically, it fits within the artist’s first and second trips to Newfoundland.

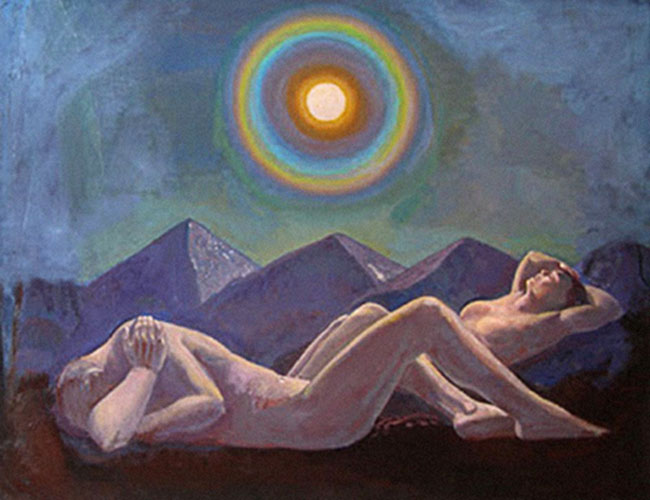

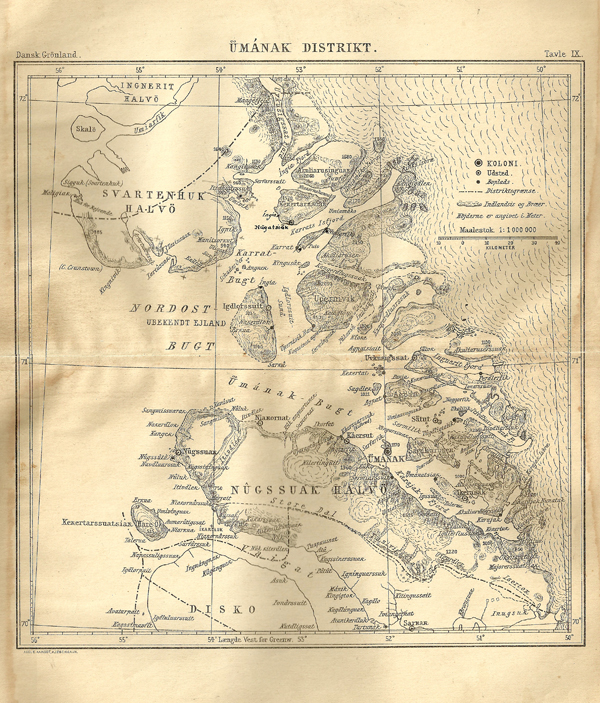

There are other works Kent created — that fit one or more of the parameters I offer above — that are not included in the catalogue raisonné: including some works that did not come to fruition until the artist’s stay in Alaska — 1918-1919. The descriptively titled painting, “Recumbent Nudes with Ringed Sun” (fig. 5), with its nude male and female figures that resemble those in Newfoundland Dirge, but with Alaskan styled peaks in the background, is a good example. (The mountain backdrop in To the Stars more closely resembles New York’s Adirondacks.)

THE SPIRITUAL

Little wonder that Kent didn’t follow Alfred Stieglitz and Marsden Hartley’s lead (as discussed by Wien, pp. 11-12) and dwell in a hub of “civilization” for inspiration: but instead followed a parallel stream of thought expressed by critic Henry McBride. Writing of Kent’s Newfoundland work McBride said that the artist “communed with himself and has apparently been interrogating the stars.” McBride beseeched artists to “get out of the rut. There are too many agencies, particularly in New York, that are calculated to make artists think alike” (McBride. The New York Sun. 4/4/1917). Kent did have one foot in the “cultured” world, but his other foot was in the “wastelands and thoughtless seas” (as, in this instance, Hartley would make us believe. Wien p. 12).

Perhaps the boldest of the author’s interpretations is his suggestion that the numerical listing of the Newfoundland exhibition brochure “offers additional insight into the way Kent and… Charles Daniel viewed the series… with titles suggesting a larger, philosophical context beyond the local and temporal.” The author suggests that the paintings The Shepherd, A Landscape, and A Young Sailor — numbers 1-3 in the brochure — represent “the ministry of Jesus”; that A Young Sailor and Man, the Abyss (3 and 6) represent “the sufferings of Jesus”; that Newfoundland Dirge and The House of Dread (4 and 5) represent “the death of Jesus and lamentations of the community”; that The Voyager Beyond Life and Ruin and Eternity (7 and 8) represent “the Resurrection”; and that A Pastoral (9) represents “the Empyrean Heaven” (Wien. p. 16)

Though the author may not have claimed that Kent was a practicing Christian, he does believe that the artist possessed “a doubting mind wrestling with doctrinaire religion,” which was now “responsive to new and radical currents of thought” (Wien. p. 17). Fair enough.

In childhood, Kent was a member in the Church of England. Into his twenties he was writing about Christianity and the teachings of Christ in relationship to his belief in socialism, “Brotherly Love,” and Labor. As he evolved away from a theistic belief system he journeyed toward pantheism. The theist sees God as the creator whereas the pantheist sees the creation as God. To quote Kent: “God had become to me the symbol of the life force of our world and universe; a name for the immense unknown. Imponderable, yet immanent in man, in beasts… in the earth, sun, moon and stars. It — I choose the impersonal pronoun as alone consistent with my faith — It was to me a force as un-moral as such manifestations of itself as storms or earthquakes, and for that very reason greatly to be feared. It was as un-moral and impersonal and splendid as its sunset’s light on land and sea — and for that reason to be reverenced. I feared and reverenced god. In fear and reverence I painted.”

WORKS MISSED OR POSSIBLY MISATTRIBUTED

As is often the case when compiling a catalogue raisonné, some works are missed. Examples of those that are not included: the descriptively titled paintings “Newfoundland Home” (fig. 6) and “Newfoundland Harbor” (fig. 7); Our front yard, Brigus, N’f’l’nd (fig. 8); and brush and ink drawings of Kent’s Newfoundland house, the harbor, a study for The Shepherd, and a theatrical appearing sketch (fig. 9 – fig. 12).

Within the author’s notes for his catalogue raisonné, and specifically regarding “Lamb and Child Beneath Crescent Moon” (number 75), he notes that two examples of the announcement were found in Kent’s daughter, Barbara Carter’s, estate. In a conversation with this author, several years ago, Barbara, a former Art Students League pupil, told me she was the author of one of these works.

A Tragedy of Newfoundland. The author refers to this writing as a “journal,” rendered in much the same manner as Kent’s autobiographical writings Wilderness, Voyaging, N by E and Salamina. The author’s understanding of this essay is incomplete: incomplete in the sense that he was limited to the resources that he notes — a manuscript, in the Carl Zigrosser Papers and a typescript in the Kent Papers, respectively, at the Archives of American Art. He was unaware of the editorial variations that are evident in the handwritten manuscript and the typescript that are in my archives.

IN CLOSING

As I stated early in this review, there is no license on interpreting an artist’s work. However, it is imperative to delineate between one’s personal interpretation and an interpretation based on evidence provided by the artist. Moreover, when compiling a catalogue raisonné, there is an obligation to present all known facts.

When one limits the scope of their catalogue raisonné to, say, geography — Newfoundland, as we examine here — versus a standard time line, confusion can arise. In this case, as I address above, there appear to be no concrete parameters on the definition of a “Newfoundland work.” And without parameters, we should consider this publication an illustrated catalogue of selected works. It has fulfilled this purpose honorably.

There are several issues that I have not addressed in this review, that are fodder for a Kent scholar to pursue: if for no better reason than to better understand Rockwell Kent and his work. I will briefly mention that, in this author’s opinion, the jury is still out on the location of such works as the descriptively titled “Woman Kneeling” and “Nude Family in Landscape”: though their timeline certainly falls within the “Newfoundland period.”

In a final note on the exhibition, “Pointed North”: The Rooms had included, in it’s “works pertaining to Kent” section of the exhibition, a watercolor of a church, signed by “Rockwell Kent.” As I am familiar with the style of rendering and the signature of this watercolor, I informed Ms. Stone that this work may have been by another Rockwell Kent but not the one featured in this exhibition. By consent with the owner, the watercolor was removed.

To close… I found this exhibition, like all Kent exhibitions, rewarding: for the simple reason that it exposes people to the life and work of an important artist, or avails them an opportunity to view the work afresh.

ADDENDA

To elaborate on the origins and use of the two parade panels…

In a 13 September 1935 letter to Donald Brace, of the publisher, Harcourt Brace and Company, Rockwell Kent mentions using the “two large decorative panels used in 1933 in Dutton’s window” as promotional props for his then latest publication, Salamina. Indeed, in a 26 September 1933 letter Kent tells Brace: “I am preparing two 8 feet long by 2 feet high panels of mountains and sea, handpainted in simple colors by R.K., for the decoration of Dutton’s window.” To which Brace replied: “…Excellent thing to have this on Fifth Avenue, and no doubt we can use them else where later.” The book they were discussing, in 1933, was Kent’s, Rockwellkentiana: Few Words and Many Pictures. Dutton’s, at that time, was located at 681 Fifth Avenue in New York City.

As we know, the panels were later used as Asgaard Farm parade props.

In Mr. Wien’s essay “Vital Passage” (p. 13 and footnote 5, p. 28), he makes reference to two small reverse paintings on glass that were purchased by Arthur Jerome Eddy: which were included in the 1922 Art Institute of Chicago’s Exhibition of Paintings from the Collection of the Late Arthur Jerome Eddy. These paintings were purchased from Knoedler Galleries in March of 1920 for $200.00.

The paintings are indeed as descriptively titled in the AIC catalogue: “Girl Tripping Downhill” (fig. 13) and “Girl Asleep Under a Tree” (fig. 14). The latter is not to be confused with the similar painting on glass, referred to as “Sleeping Maiden with Book,” that accompanies Mr. Wien’s other essays–The Magazine Antiques, July 2005, p. 70; and Rockwell Kent; The Mythic and the Modern, Portland Museum of Art, 2005, p. 93).

The bibliography on page 75 lists my book, Rockwell Kent’s Forgotten Landscapes (Down East Books. 1998) but fails to include the name of my co-author, Ellen Pearce.

My thanks to Betty Badcock. In memory of Peter Roberts.

© Scott R. Ferris

Mr. Kent Goes to Washington (Again)

Mr. Kent Goes to Washington (Again)

A GIFT TO THE AMERICAN PEOPLE

When the new gift of Rockwell Kent’s oil painting, Citadel, goes on display at the National Gallery of Art, it will not be the first time that Kent has made an appearance in our Nation’s capital. In fact, it will not be the first time that this painting has been displayed, publicly or privately, in Washington, DC.

It could be said that Kent made notable appearances in DC on three previous occasions: the first being while under the patronage of Duncan Phillips — the grand patron of American art, whose self named museum, The Phillips Collection, once boasted ownership of at least 15 oil paintings, drawings, watercolors and prints by the artist.

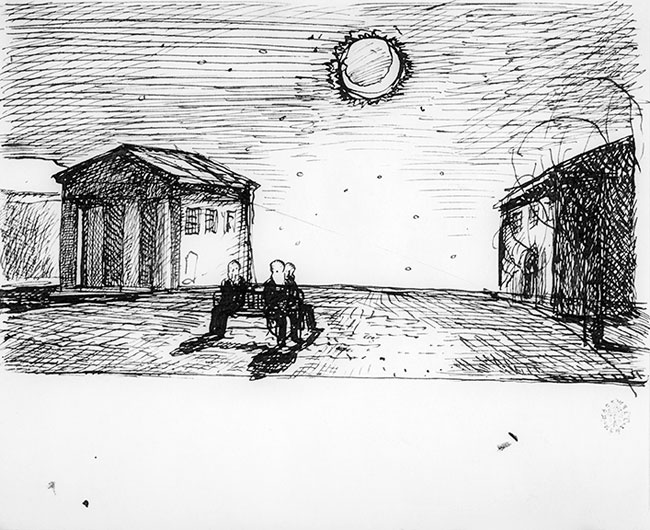

Kent’s second notable presence came on two occasions in 1937 when, one, his highly controversial mural for the Benjamin Franklin Post Office was unveiled — this two-panel mural was commonly referred to as the “let us change chief’s” mural because of its overt support of independence for Puerto Rico; and two, the Gallery of Modern Masters hosted “Greenland Paintings and Prints: Rockwell Kent.” Of the 19 paintings and 10 prints that were on display, prints were the only works that sold. (Citadel had been priced at $1800.)

Kent’s third most memorable appearance occurred in 1953 when the artist was summoned to appear before Senator Joseph McCarthy and the Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations on “charges” that he was a communist. Kent took the Fifth Amendment before the Committee but once outside the hall he proclaimed to the world, via television, that “I am not now and I never have been a member of the Communist Party.”

Just prior to Kent’s confrontation with Senator McCarthy he was under surveillance for his association with numerous “leftist” causes — he was a protagonist for innumerable unions; during Christmas of 1942 he hosted Soviet students from Columbia University; he attended meetings of the World Congress for Peace in Europe and the Soviet Union in 1949 and 1950, and the list went on. Due, in part, to his prominence in these so-called leftist causes, Kent found a patron in J. J. (Joseph James or “Jim”) Ryan, a descendant of Thomas Fortune Ryan, the multi-millionaire financier.

On 16 September 1950, Robert McIntyre, of the prominent New York City gallery William Macbeth, wrote a letter to Kent seeking artwork for one of his clients. From an initial purchase of 3 paintings J. J. Ryan came to acquire more than 30 oils, including Citadel, and several other works. Thus began the patronage that supported Kent through the tumultuous decade of the 1950s: through a decade of litigation, — the prolonged case that ultimately concluded at the U. S. Supreme Court: a case that became known as “The Right to Travel” — and a virtual boycott of his artwork in commercial and arts venues.

Several of Ryan’s Kents — including Citadel, Blue Day, Gray Day, North, and May, North Greenland — are among the best works the artist created, and were highlighted in Kent’s autobiography, It’s Me O Lord.

By the turn of the century four of these paintings were acquired by collectors Ed and Deborah Shein. Ed, under his firm American Art Search, was no newcomer to Kent: he had brokered several Kent paintings throughout his 40 years in the business, — “Neither Snow, Nor Rain, Nor Ice,” Croquet, Artist in Greenland, Headlands and Sea — while also marketing other important 19th and 20th century artists/paintings.